Actually we have 2 crises occurring at the same time—one short-term and one long-term.

Actually we have 2 crises occurring at the same time—one short-term and one long-term.

Let’s look at each:

A. The Short-term Crisis, in as few words as possible:

- A multi-year period of unprofitable prices caused the supply of US lambs to shrink. By 2009 demand for lamb exceeded supply.

- This caused live lamb prices to rise—eventually reaching record levels in 2011. Producers were happy—briefly.

- However, record live lamb prices caused wholesale and retail prices for US lamb to also rise to record levels.

- Very high US lamb prices encouraged retail and food service lamb buyers to do two things:

- Switch to imported lamb (which is almost always less expensive than US lamb).

- Stop offering lamb altogether.

This, in turn, caused a drop in demand for US lamb. When the demand fell below supply, the prices for live lambs and feeder lambs collapsed. Purely by chance, this price collapse occurred simultaneously with a widespread drought and high grain prices—which forced up the cost of feeding lambs and ewe flocks across the USA.

The short-term solution to this US lamb crisis is embedded within itself. Serious financial losses by US sheep producers will cause many lamb producers and feeders to switch to other uses for their time, land and $$. So US lamb production will decline further until the supply is less than the demand. And so the multi-year cycle will begin again.

How long will this take? The financial pain this time is major. So the shrinkage in supply may be more rapid than usual.

B. The Long-Term Crisis:

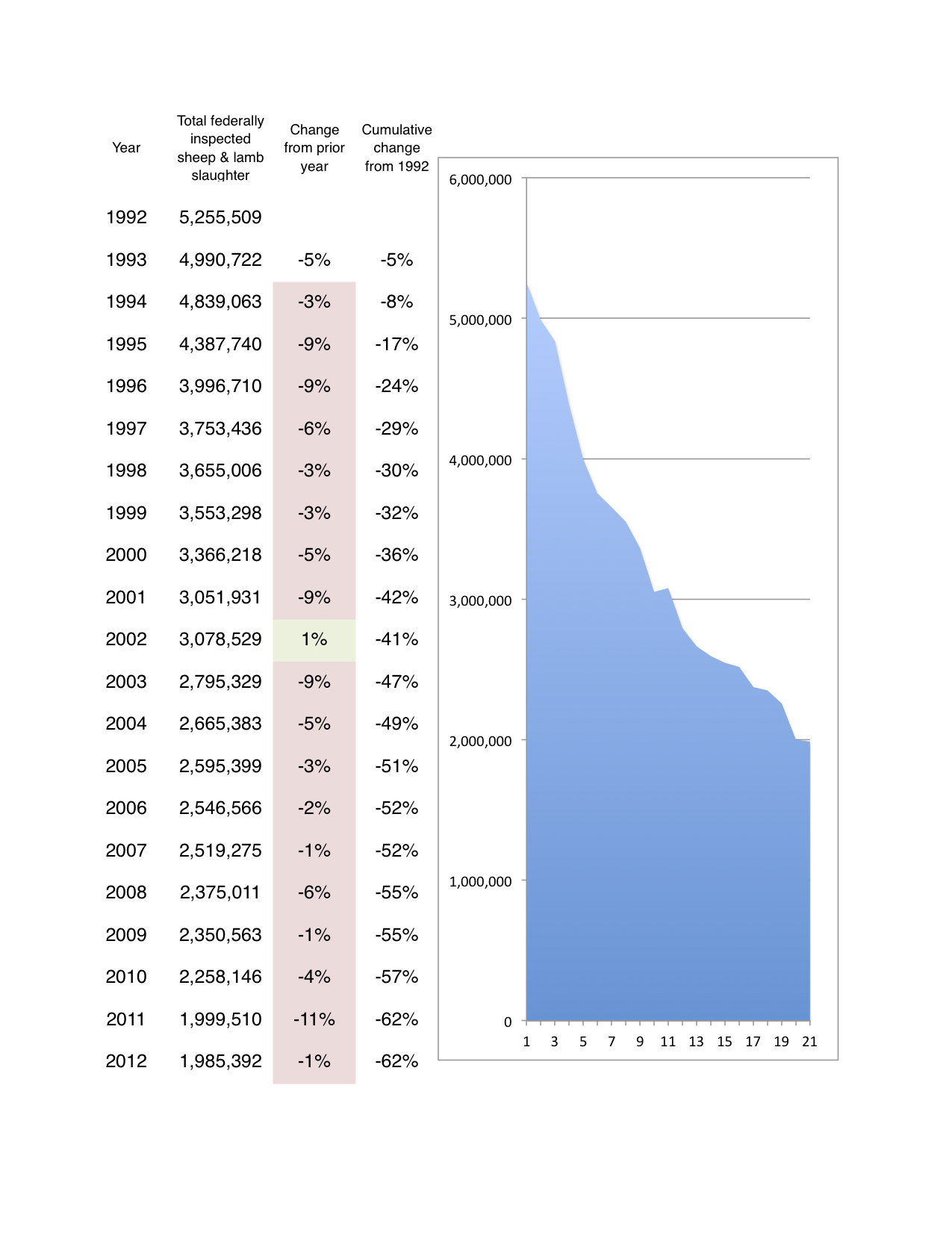

Such is the pain of the short-term crisis that it’s easy to overlook that both the demand and supply of US lamb has been dropping for decades. The table & matching graph below illustrate it better than any words can. (To provide a complete 2012 picture I replicated the kills for Oct, Nov and Dec from 2011.)

As you can see, federally inspected sheep slaughter has dropped by 62% in 21 years. The decline is actually greater than 62% because the US population has grown by 20% over 2 decades (from 252 million in 1991 to over 310 million) while the sheep slaughter has been declining. So the decline adjusted for the population growth the decline is 68%.

I can’t think of any food industry that has declined that fast over two decades.

Here are possible causes for this decline along with my comments. They are not in order of importance because many are not quantifiable.

- It may not be quite as bad as it appears. The non-traditional demand for sheep meat has grown over the same 2 decades. We’re told that much of this demand bypasses federal inspection. This means that these lambs are not included in the table and graph above. How many sheep are involved? No one knows for sure. Some suggest it now could be as high as 1/3 of all sheep slaughtered in the USA. That would be 1 million sheep annually. Remember, however, that this “hidden” market also existed in 1991—though it was smaller. If it’s twice as large as it was in 1991 the increase would be 500,000 sheep/year. A big number, yes. But the population growth adjustment (if US sheep slaughter had kept pace with population change from 1991 to 2012) is more than twice this total (1,150,000 sheep). So it may be a mistake to focus too much attention here. The real problem, in my view, is the US lamb’s loss of market share to other meats and to imported lamb.

- The loss of the wool subsidy. It occurred in 1993/94. Its impact would be spread over the next 5 years. However the rapidly shrinking sheep slaughter numbers has carried on long past 1998.

- The arrival of imported lamb from New Zealand and Australia. Though always present, it began in earnest in the 90’s—aided by a strong US $. Initially US producers were assured that our lamb was much better than imported lamb. However it seems lamb buyers at the retail (food-store) and food-service level (restaurants) felt otherwise because roughly half the lamb consumed in the USA is now imported lamb.

- Predators (coyotes, wolves, cougars) issues have increased. There is no question that they are a cost to US lamb producers that US meat producers (cattle, pigs, veal, chicken, turkey) and imported lamb producers don’t share to the same extent.

- US lamb at the wholesale and retail levels is considerably more expensive per lb. than imported lamb or other US meats. Though it varies by the primal cut and the season I’m told that is often 20% more expensive than imported lamb at wholesale levels.

- US lamb carcasses, primals and cuts are too big. The average US lamb carcass always was bigger and heavier than imported lamb. And the average US lamb carcass has increased in size and weight – from 60 lbs to 75 lbs. At 60 lbs they already were considerably larger than found anywhere else in the developed world (where 35- 50 lbs is the norm). Some experts suggest that being larger helps US lamb compete with imported lamb. However it also means that a US lamb chop, rack, cutlet or leg that weighs 33% more than an imported lamb chop and also costs 20% more per lb costs, in the end, 60% more than the imported lamb alternative. (Please appreciate that I don’t claim any expertise in this area other than a serious interest in the subject.)

- US lamb is less consistent in size, availability, and probable eating & cooking experience than either imported lamb or other US meats (pork, chicken, turkey, beef). I’m not the first to note this. Why is it less consistent? For a start consider the wide array of US genetics and production systems. Also that USA lamb is often not the primary product of US breeding flocks. Instead it is often a by-product of the show sheep industry, a by-product of the fiber sheep industries, a by-product of the dairy sheep industry, etc. Imported lamb that enters this country, on the other hand, is usually the primary product of the producers supplying it. Their genetics and production systems are focused tightly on providing the very best lamb.

There are others—but this list is long enough already…

What can be done to turn around this decades long decline?

Because this note is long already—I’ll post my views to the Guide in a few weeks time.